If the road we are currently on leads to the likely end of our civilization, how do we change roads?

Suppose the desire to stop developing AGI and superintelligence were widespread and powerful,87 because it becomes common understanding that AGI would be power-absorbing rather than power-granting, and a profound danger to society and humanity. How would we close the Gates?

At present we know of only one way to make powerful and general AI, which is via truly massive computations of deep neural networks. Because these are incredibly difficult and expensive things to do, there is a sense in which not doing them is easy.88 But we have already seen the forces that are driving toward AGI, and the game-theoretic dynamics that make it very difficult for any party to unilaterally stop. So it would take a combination of intervention from the outside (i.e. governments) to stop corporations, and agreements between governments to stop themselves.89 What could this look like?

It is useful first to distinguish between AI developments that must be prevented or prohibited, and those that must be managed. The first would primarily be runaway to superintelligence.90 For prohibited development, definitions should be as crisp as possible, and both verification and enforcement should be practical. What must be managed would be general, powerful AI systems – which we already have, and that will have many gray areas, nuance, and complexity. For these, strong effective institutions are crucial.

We may also usefully delineate issues that must be addressed at an international level (including between geopolitical rivals or adversaries)91 from those that individual jurisdictions, countries, or collections of countries can manage. Prohibited development largely falls into the “international” category, because a local prohibition on the development of a technology can generally be circumvented by changing location.92

Finally, we can consider tools in the toolbox. There are many, including technical tools, soft law (standards, norms, etc., hard law (regulations and requirements), liability, market incentives, and so on. Let’s put special attention on one that is particular to AI.

Compute security and governance

A core tool in governing high-powered AI will be the hardware it requires. Software proliferates easily, has near-zero marginal production cost, crosses borders trivially, and can be instantly modified; none of these are true of hardware. Yet as we’ve discussed, huge amounts of this “compute” are necessary during both training of AI systems and during inference to achieve the most capable systems. Compute can be easily quantified, accounted, and audited, with relatively little ambiguity once good rules for doing so are developed. Most crucially, large amounts of computation are, like enriched uranium, a very scarce, expensive and hard-to-produce resource. Although computer chips are ubiquitous, the hardware required for AI is expensive and enormously difficult to manufacture.93

What makes AI-specialized chips far more manageable as a scarce resource than uranium is that they can include hardware-based security mechanisms. Most modern cellphones, and some laptops, have specialized on-chip hardware features that allow them to ensure that they install only approved operating system software and updates, that they retain and protect sensitive biometric data on-device, and that they can be rendered useless to anyone but their owner if lost or stolen. Over the past several years such hardware security measures have become well-established and widely adopted, and generally proven quite secure.

The key novelty of these features is that they bind hardware and software together using cryptography.94 That is, just having a particular piece of computer hardware does not mean that a user can do anything they want with it by applying different software. And this binding also provides powerful security because many attacks would require a breach of hardware rather than just software security.

Several recent reports (e.g. from GovAI and collaborators, CNAS, and RAND) have pointed out that similar hardware features embedded in cutting edge AI-relevant computing hardware could play an extremely useful role in AI security and governance. They enable a number of functions available to a “governor”95 that one might not guess were available or even possible. As some key examples:

- Geolocation: Systems can be set up so that chips have a known location, and can act differently (or be shut off altogether) based upon location.96

- Allow-listed connections: each chip can be configured with a hardware-enforced allow-list of particular other chips with which it can network, and be unable to connect with any chips not on this list.97 This can cap the size of communicative clusters of chips.98

- Metered inference or training (and auto-offswitch): A governor can license only a certain amount of training or inference (in time, or FLOPs, or possibly tokens) to be performed by a user, after which new permission is required. If the increments are small, then relatively continuous re-licensing of a model is required. The model can then be “turned off” simply by withholding this license signal.99

- Speed limit: A model is prevented from running at higher inference speed than some limit that is determined by a governor or otherwise. This could be implemented via a limited set of allow-listed connections, or by more sophisticated means.

- Attested training: A training procedure can yield cryptographically secure proof that a particular set of codes, data, and amount of compute usage were employed in generation of the model.

How to not build superintelligence: global limits on training and inference compute

With these considerations – especially regarding computation – in place, we can discuss how to close the Gates to artificial superintelligence; we’ll then turn to preventing full AGI, and managing AI models as they approach and exceed human capability in different aspects.

The first ingredient is, of course, the understanding that superintelligence would not be controllable, and that its consequences are fundamentally unpredictable. At least China and the US must independently decide, for this or other purposes, not to build superintelligence.100 Then an international agreement between them and others, with a strong verification and enforcement mechanism, is needed to assure all parties that their rivals are not defecting and deciding to roll the dice.

To be verifiable and enforceable the limits should be hard limits, and as unambiguous as possible. This seems like a virtually impossible problem: limiting the capabilities of complex software with unpredictable properties, worldwide. Fortunately the situation is much better than this, because the very thing that has made advanced AI possible – a huge amount of compute – is much, much easier to control. Although it might still allow some powerful and dangerous systems, runaway superintelligence can likely be prevented by a hard cap on the amount of computation that goes into a neural network, along with a rate limit on the amount of inference that an AI system (of connected neural networks and other software) can perform. A specific version of this is proposed below.

It may seem that placing hard global limits on AI computation would require huge levels of international coordination and intrusive, privacy-shattering surveillance. Fortunately, it would not. The extremely tight and bottle-necked supply chain provides that once a limit is set legally (whether by law or executive order), verification of compliance to that limit would only require involvement and cooperation of a handful of large companies.101

A plan like this has a number of highly desirable features. It is minimally invasive in the sense that only a few major companies have requirements placed on them, and only fairly significant clusters of computation would be governed. The relevant chips already contain the hardware capabilities needed for a first version.102 Both implementation and enforcement rely on standard legal restrictions. But these are backed up by terms-of-use of the hardware and by hardware controls, vastly simplifying enforcement and forestalling cheating by companies, private groups, or even countries. There is ample precedent for hardware companies placing remote restrictions on their hardware usage, and locking/unlocking particular capabilities externally,103 including even in high-powered CPUs in data centers.104 Even for the rather small fraction of hardware and organizations affected, the oversight could be limited to telemetry, with no direct access to data or models themselves; and the software for this could be open to inspection to exhibit that no additional data is being recorded. The schema is international and cooperative, and quite flexible and extensible. Because the limit chiefly is on hardware rather than software, it is relatively agnostic as to how AI software development and deployment occurs, and is compatible with variety of paradigms including more “decentralized” or “public” AI aimed combating AI-driven concentration of power.

A computation-based Gate closure does have drawbacks as well. First, it is far from a full solution to the problem of AI governance in general. Second, as computer hardware gets faster, the system would “catch” more and more hardware in smaller and smaller clusters (or even individual GPUs).105 It is also possible that due to algorithmic improvements an even lower computation limit would in time be necessary,106 or that computation amount becomes largely irrelevant and closing the Gate would instead necessitate a more detailed risk-based or capability-base governance regime for AI. Third, no matter the guarantees and the small number of entities affected, such a system is bound to create push-back regarding privacy and surveillance, among other concerns.107

Of course, developing and implementing a compute-limiting governance scheme in a short time period will be quite challenging. But it absolutely is doable.

A-G-I: The triple-intersection as the basis of risk, and of policy

Let us now turn to AGI. Hard lines and definitions here are more difficult, because we certainly have intelligence that is artificial and general, and by no extant definition will everyone agree if or when it exists. Moreover, a compute or inference limit is a somewhat blunt tool (compute being a proxy for capability, which is then a proxy for risk) that – unless it is quite low – is unlikely to prevent AGI that is powerful enough to cause social or civilizational disruption or acute risks.

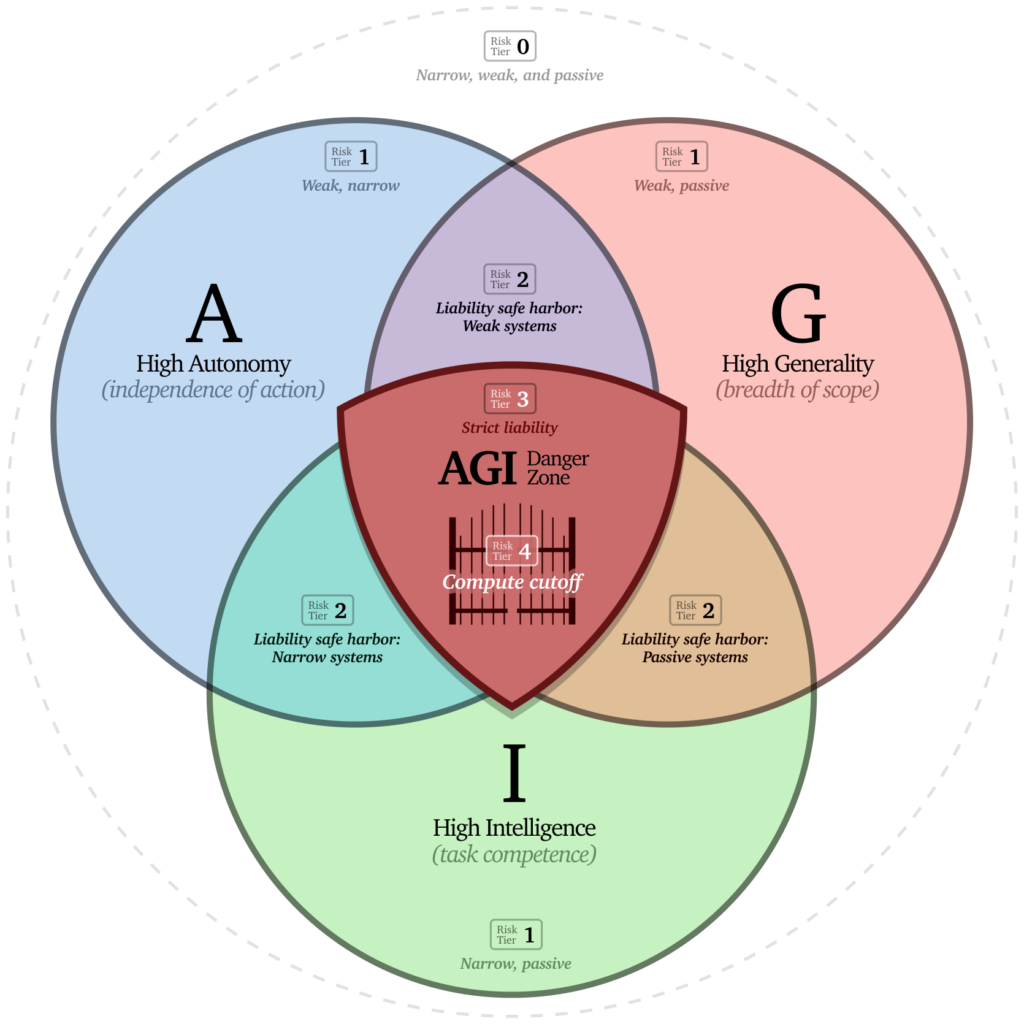

I’ve argued that the most acute risks emerge from the triple-intersection of very high capability, high autonomy, and great generality. These are the systems that – if they are developed at all – must be managed with enormous care. By creating stringent standards (through liability and regulation) for systems combining all three properties, we can channel AI development toward safer alternatives.

As with other industries and products that could potentially harm consumers or the public, AI systems require careful regulation by effective and empowered government agencies. This regulation should recognize the inherent risks of AGI, and prevent unacceptably risky high-powered AI systems from being developed.108

However, large-scale regulation, especially with real teeth that are sure to be opposed by industry,109 takes time110 as well as political conviction that it is necessary.111 Given the pace of progress, this may take more time than we have available.

On a much faster timescale and as regulatory measures are being developed, we can give companies the necessary incentives to (a) desist from very high-risk activities and (b) develop comprehensive systems for assessing and mitigating risk, by clarifying and increasing liability levels for the most dangerous systems. The idea would be to impose the very highest levels of liability – strict and in some cases personal criminal – for systems in the triple-intersection of high autonomy-generality-intelligence, but to provide “safe harbors” to more typical fault-based liability for systems in which one of those properties is lacking or guaranteed to be manageable. That is, for example, a “weak” system that is general and autonomous (like a capable and trustworthy but limited personal assistant) would be subject to lower liability levels. Likewise a narrow and autonomous system like a self-driving car would still be subject to the significant regulation it already is, but not enhanced liability. Similarly for a highly capable and general system that is “passive” and largely incapable of independent action. Systems lacking two of the three properties are yet more manageable and safe harbors would be even easier to claim. This approach mirrors how we handle other potentially dangerous technologies:112 higher liability for more dangerous configurations creates natural incentives for safer alternatives.

The default outcome of such high levels of liability, which act to internalize AGI risk to companies rather than offload it to the public, is likely (and hopefully!) for companies to simply not develop full AGI until and unless they can genuinely make it trustworthy, safe, and controllable given that their own leadership are the parties at risk. (In case this is not sufficient, the legislation clarifying liability should also explicitly allow for injunctive relief, i.e. a judge ordering a halt, for activities that are clearly in the danger zone and arguably pose a public risk.) As regulation comes into place, abiding by regulation can become the safe harbor, and the safe harbors from low autonomy, narrowness, or weakness of AI systems can convert into relatively lighter regulatory regimes.

Key provisions of a Gate closure

With the above discussion in mind, this section provides proposals for key provisions that would implement and maintain prohibition on full AGI and superintelligence, and management of human-competitive or expert-competitive general-purpose AI near the full AGI threshold.113 It has four key pieces: 1) compute accounting and oversight, 2) compute caps in training and operation of AI, 3) a liability framework, and 4) tiered safety and security standards defined that include hard regulatory requirements. These are succinctly described next, with further details or implementation examples given in three accompanying tables. Importantly, note that these are far from all that will be necessary to govern advanced AI systems; while they will have additional security and safety benefits, they are aimed at closing the Gate to intelligence runaway, and redirecting AI development in a better direction.

1. Compute accounting, and transparency

- A standards organization (e.g. NIST in the US followed by ISO/IEEE internationally) should codify a detailed technical standard for the total compute used in training and operating AI models, in FLOP, and the speed in FLOP/s at which they operate. Details for what this could look like are given in Appendix A.114

- A requirement – either by new legislation or under existing authority115 – should be imposed by jurisdictions in which large-scale AI training takes place to compute and report to a regulatory body or other agency the total FLOP used in training and operating all models above a threshold of 1025 FLOP or 1018 FLOP/s.116

- These requirements should be phased in, initially requiring well-documented good-faith estimates on a quarterly basis, with later phases requiring progressively higher standards, up to cryptographically attested total FLOP and FLOP/s attached to each model output.

- These reports should be complemented by well-documented estimates of marginal energy and financial cost used in generating each AI output.

Rationale: These well-computed and transparently reported numbers would provide the basis for training and operation caps, as well as a safe harbor from higher liability measures (see Appendixes C and D).

2. Training and operation compute caps

- Jurisdictions hosting AI systems should impose a hard limit on the total compute going into any AI model output, starting at 1027 FLOP117 and adjustable as appropriate.

- Jurisdictions hosting AI systems should impose a hard limit on the compute rate of AI model outputs, starting at 1020 FLOP/s and adjustable as appropriate.

Rationale: Total computation, while very imperfect, is a proxy for AI capability (and risk) that is concretely measurable and verifiable, so provides a hard backstop for limiting capabilities. A concrete implementation proposal is given in Appendix B.

3. Enhanced liability for dangerous systems

- Creation and operation118 of an advanced AI system that is highly general, capable, and autonomous, should be legally clarified via legislation to be subject to strict, joint-and-several, rather than single-party fault-based, liability.119

- A legal process should be available to make affirmative safety cases, which would grant safe harbor from strict liability for systems that are small (in terms of compute), weak, narrow, passive, or that have sufficient safety, security, and controllability guarantees.

- An explicit pathway and set of conditions for injunctive relief to stop AI training and inference activities that constitute a public danger should be outlined.

Rationale: AI systems cannot be held responsible, so we must hold human individuals and organizations responsible for harm they cause (liability).120 Uncontrollable AGI is a threat to society and civilization and in the absence of a safety case should be considered abnormally dangerous. Putting the burden of responsibility on developers to show that powerful models are safe enough not to be considered “abnormally dangerous” incentivizes safe development, along with transparency and record-keeping to claim those safe harbors. Regulation can then prevent harm where deterrence from liability is insufficient. Finally, AI developers are already liable for damages they cause, so legally clarifying liability for the most risky of systems can be done immediately, without highly detailed standards being developed; these can then develop over time. Details are given in Appendix C.

4. Safety regulation for AI

A regulatory system that addresses large-scale acute risks of AI will require at minimum:

- The identification or creation of an appropriate set of regulatory bodies, probably a new agency;

- A comprehensive risk assessment framework;121

- A framework for affirmative safety cases, based in part on the risk assessment framework, to be made by developers, and for auditing by independent groups and agencies;

- A tiered licensing system, with tiers tracking levels of capability.122 Licenses would granted on the basis of safety cases and audits, for development and deployment of systems. Requirements would range from notification at the low end, to quantitative safety, security, and controllability guarantees before development, at the top end. These would prevent release of systems until they are demonstrated safe, and prohibit the development of intrinsically unsafe systems. Appendix D provides a proposal for what such safety and security standards could entail.

- Agreements to bring such measures to the international level, including international bodies to harmonize norms and standards, an potentially international agencies to review safety cases.

Rationale: Ultimately, liability is not the right mechanism for preventing large-scale risk to the public from a new technology. Comprehensive regulation, with empowered regulatory bodies, will be needed for AI just as for every other major industry posing a risk to the public.123

Regulation toward preventing other pervasive but less acute risks is likely to vary in its form from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. The crucial thing is to avoid developing the AI systems that are so risky that these risks are unmanageable.

What then?

Over the next decade, as AI becomes more pervasive and the core technology advances, two key things are likely to happen. First, regulation of existing powerful AI systems will become more difficult, yet even more necessary. It is likely that at least some measures addressing large-scale safety risks will require agreement at the international level, with individual jurisdictions enforcing rules based on international agreements.

Second, training and operation compute caps will become harder to maintain as hardware becomes cheaper and more cost efficient; they may also become less relevant (or need to be even tighter) with advances in algorithms and architectures.

That controlling AI will become harder does not mean we should give up! Implementing the plan outlined in this essay would give us both valuable time and crucial control over the process that would put us in a far, far better position to avoid the existential risk of AI to our society, civilization, and species.

In the yet longer term, there will be choices to make as to what we allow. We may choose still to create some form of genuinely controllable AGI, to the degree this proves possible. Or we may decide that running the world is better left to the machines, if we can convince ourselves that they will do a better job of it, and treat us well. But these should be decisions made with deep scientific understanding of AI in hand, and after meaningful global inclusive discussion, not in a race between tech moguls with most of humanity completely uninvolved and unaware.

- Most likely, the spread of this realization will take either intense effort by education and advocacy groups making this case, or a pretty significant AI-caused disaster. We can hope it will be the former.↩︎

- Paradoxically, we are used to Nature limiting our technology by making it very hard to develop, especially scientifically. But that’s no longer the case for AI: the key scientific problems are turning out to be easier than anticipated. We cannot count on Nature saving us from ourselves here – we will have to do so.↩︎

- Where, exactly, do we stop in developing new systems? Here, we should adopt a precautionary principle. Once a system is deployed, and especially once that level of system capability proliferates, it is exceedingly difficult to roll back. And if a system is developed (especially at great cost and effort), there will be enormous pressure to use or deploy it, and temptation for it to be leaked or stolen. Developing systems and then deciding whether they are deeply unsafe is a dangerous road.↩︎

- It would also be wise to forbid AI development that is intrinsically dangerous, such as self-replicating and evolving systems, those designed to escape enclosure, those that can autonomously self-improve, deliberately deceptive and malicious AI, etc.↩︎

- Note this does not necessarily mean enforced at the international level by some sort of global body: instead sovereign nations could enforce agreed-upon rules, as in many treaties.↩︎

- As we’ll see below, the nature of AI computation would allow something of a hybrid; but international cooperation will still be needed.↩︎

- For example, the machines required to etch AI-relevant chips are made by only one firm, ASML (despite many other attempts to do so), the vast majority of relevant chips are manufactured by one firm, TSMC (despite others attempting to compete), and the design and construction of hardware from those chips done by just a few including NVIDIA, AMD, and Google.↩︎

- Most importantly, each chip holds a unique and inaccessible cryptographic private key it can use to “sign” things.↩︎

- By default this would the company selling the chips, but other models are possible and potentially useful.↩︎

- A governor can ascertain a chip’s location by timing the exchange of signed messages with it: the finite speed of light requires the chip to be within a given radius r of a “station” if it can return a signed message in a time less than r/c, where c is the speed of light. Using multiple stations, and some understanding of network characteristics, the location of the chip can be determined. The beauty of this method is that most of its security is supplied by the laws of physics. Other methods could use GPS, inertial tracking, and similar technologies.↩︎

- Alternatively, pairs of chips could be allowed to communicate with each other only via explicit permission of a governor.↩︎

- This is crucial because at least currently, very high bandwidth connection between chips is needed to train large AI models on them.↩︎

- This could also be set up to require signed messages from N of M different governors, allowing multiple parties to share governance.↩︎

- This is far from unprecedented – for example militaries have not developed armies of cloned or genetically engineered supersoldiers, though this is probably technologically possible. But they have chosen not to do this, rather than being prevented by others. The track record isn’t great for major world powers being prevented from developing a technology they strongly wish to develop.↩︎

- With a couple of notable exceptions (in particular NVIDIA) the AI-specialized hardware is a relatively small part of these companies’ overall business and revenue model. Moreover, the gap between hardware used in advanced AI and “consumer grade” hardware is significant, so most consumers of computer hardware would be largely unaffected.↩︎

- For more detailed analysis, see the recent reports from RAND and CNAS. These focus on technical feasibility, especially in the context of US export controls seeking to constrain other countries’ capacity in high-end computation; but this has obvious overlap with the global constraint envisaged here.↩︎

- Apple devices, for example, are remotely and securely locked when reported lost or stolen, and can be re-activated remotely. This relies on the same hardware security features discussed here.↩︎

- See e.g. IBM’s capacity on demand offering, Intel’s Intel on demand., and Apple’s private cloud compute.↩︎

- This study shows that historically the same performance has been achieved using about 30% less dollars per year. If this trend continues, there may be significant overlap between AI and “consumer” chip use, and in general the amount of needed hardware for high-powered AI systems could become uncomfortably small.↩︎

- Per the same study, given performance on image recognition has required 2.5x less computation each year. If this were to also hold for the most capable AI systems as well, a computation limit would not be a useful one for very long.↩︎

- In particular, at the country level this looks a lot like a nationalization of computation, in that the government would have a lot of control over how computational power gets used. However, for those worried about government involvement, this seems far safer than and preferable to the most powerful AI software itself being nationalized via some merger between major AI companies and national governments, as some are starting to advocate for.↩︎

- A major regulatory step in Europe was taken with the 2024 passage of the EU AI Act. It classifies AI by risk: prohibiting unacceptable systems, regulating high-risk ones, and imposing transparency rules, or no measures at all, upon low-risk systems. It will significantly reduce some AI risks, and boost AI transparency even for US firms, but has two key flaws. First, limited reach: while it applies to any company providing AI in the EU, enforcement over US-based firms is weak, and military AI is exempt. Second, while it covers GPAI, it fails to recognize AGI or superintelligence as unacceptable risks or prevent their development—only their EU deployment. As a result, it does little to curb the risks of AGI or superintelligence.↩︎

- Companies often represent that they are in favor of reasonable regulation. But somehow they nearly always seem to oppose any particular regulation; witness the fight over the quite low-touch SB1047, which most AI companies publicly or privately opposed.↩︎

- It was about 3 1/2 years from the time the EU AI act was proposed until it went into effect.↩︎

- It’s sometimes expressed that it’s “too early” to start regulating AI. Given the last note, that hardly seems likely. Another expressed concern is that regulation would “harm innovation.” But good regulation just changes the direction, not amount, of innovation.↩︎

- An interesting precedent is in the transport of hazardous materials, which might escape and cause damage. Here, regulation and case law have established strict liability for very hazardous materials like explosives, gasoline, poisons, infectious agents, and radioactive waste. Other examples include warnings on pharmaceuticals, classes of medical devices, etc.↩︎

- Another comprehensive proposal with similar aims put forth in “A Narrow Path” advocates for a more centralized, prohibition-based approach that funnels all frontier AI development through a single international entity, overseen by strong international institutions, with clear categorical prohibitions rather than graduated restrictions. I’d also endorse that plan; however it will take even more political will and coordination than the one proposed here.↩︎

- Some guidelines for such a standard were published by the Frontier Model Forum. Relative to the proposal here, those err on the side of less precision and less compute included in the tally.↩︎

- The 2023 US AI executive order (now rescinded) required similar but less fine-grained reporting. This should be strengthened by a replacing order.↩︎

- Very roughly, for now-common H100 chips this corresponds to clusters of about 1000 doing inference; it is about 100 (about USD $5M worth) of the very newest top-of-the line NVIDIA B200 chips doing inference. In both cases the training number corresponds to that cluster computing for several months month.↩︎

- This amount is larger than any currently trained AI system; a larger or smaller number might be justified as we better understand how AI capability scales with compute.↩︎

- This applies to those creating and providing/hosting the models, not end users.↩︎

- Roughly, “strict” liability means that developers are held responsible for harms done by a product by default and is a standard used for “abnormally dangerous” products, and (somewhat amusingly but appropriately) wild animals. “Joint and several” liability means that liability is assigned to all of the parties responsible for a product, and those parties have to sort out amongst themselves who carries what responsibility. This is important for systems like AI with a long and complex value chain.↩︎

- Standard fault-based single-party liability is not enough: fault will be both difficult to trace and assign because AI systems are complex, their operation is not understood, and many parties may be involved in creation of a dangerous system or output. In addition, lawsuits will take years to adjudicate and likely result merely in fines that are inconsequential to these companies, so personal liability for executives is important as well.↩︎

- There should be no exemption from safety criteria for open-weight models. Moreover, in assessing risk it should be assumed that guardrails that can be removed will be removed from widely available models, and that even closed models will proliferate unless there is a very high assurance they will stay secure.↩︎

- The scheme proposed here has regulatory scrutiny triggered on general capability; however it makes sense for some especially risky use cases to trigger more scrutiny – for example an expert virology AI system, even if narrow and passive, should probably go in a higher tier. The former US executive order had some of this structure for biological capabilities.↩︎

- Two clear examples are aviation and medicines, regulated by the FAA and FDA, and similar agencies in other countries. These agencies are imperfect, but have been absolutely vital for the functioning and success of those industries.↩︎